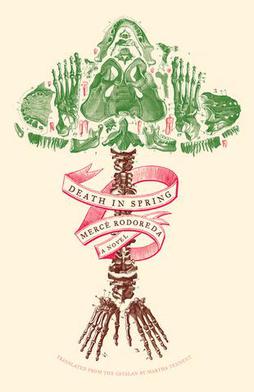

Mercè Rodoreda’s Death in Spring is a gorgeously written novel concerned with the influence society holds on the individual. In a village secluded in the mountains, its inhabitants maintain bizarre rituals; they lock their children in cupboards, imprison thieves in inhumane cages, and bury their dead in hollowed out trees.

Moments from the village is the cemetery: a grove of trees that contain upright, decaying bodies. They also contain dried cement, which is poured down the person’s throat moments before death to preserve their soul. Butterflies cover the openings left in the tree trunks, feeding on the remains of the villagers that seep through the cracks.

A young boy – acutely aware of the grotesque rituals of his village – has his own tree waiting for him. The town’s blacksmith forged a plaque and assigned him the tree on the day of his birth. He must come of age in this cruel, vindictive society obsessed with death and suffering.

Death in Spring is both elegant and gruesome, comforting and frightening, real and unimaginable. Rodoreda wrote the novel after returning to Barcelona from exile following the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship. Given the atrocities committed during that time, it’s easy to make a comparison between that society and the one portrayed in the novel.

However, Death in Spring shouldn’t be read simply as a historical piece; it’s a deeply philosophical and emotional work that extends far beyond any time or place. It looks at repression, pain, and sorrow, all obscured by the beauty of spring.

Plot

The village is nestled in the mountains, mostly likely the Pyranees that separate continental Europe from the Iberian Penninsula. Its buildings are stone and wrapped in wisteria vines. A river snakes and flows beneath the village.

Hidden behind this beautiful façade of nature is an unnatural, grotesque society. Children are locked in cupboards to wait until their parents return home. Thieves are placed in cages built for wild animals and visited by families on Sundays, as if they were a spectacle to watch. Disfigured men are shunned from the town and forced to live and sleep in the stables.

The narrator – an adolescent boy at the beginning of the story – is aware that his village’s customs are strange. When the adults lock their children up and leave their homes, he sneaks into their houses to release the children.

The town is run by the blacksmith. He is a self-imposed leader that the townsfolk look up to. He therefore leads the townsfolk to perpetuate their bizarre rituals. He tells the narrator about the cemetery.

As the sparks flew from the forge, the blacksmith told me: you too have your tree, your ring, and your plaque. I did it when you were born. When someone is born, I make their ring and plaque right away. Don’t tell anyone I told you. All of use have our ring, our plaque, and our tree. And at the entrance to the forest stand the pitchfork and the axe.

As a curious, adolescent boy, the narrator goes out to discover the cemetery. He sees a man taking an axe to one of the trees, cutting a cross into it. He sees the man peel back the bark and step into the tree to die.

I was frightened…I threw myself to the ground, on top of the pebbles, my heart drained of blood, my hands icy. I was fourteen years old, and the man who had entered the tree to die was my father.

He runs back into town and tells the blacksmith what he saw. The blacksmith calls for the village to follow him. They get to the tree that the boy’s father is dying in. They pry open the trunk and pull him out. Here, we get the first glimpse of what the town is really like.

They started to shout. They shouted at my father who had little remaining breath and was clearly near his end. He was still alive, but only his own death kept him alive. They dragged him from the tree, laid him on the ground, and began beating him. The last blows made no sound. Don’t kill him, shouted the cement man. The mortar trough, filled with rose-colored cement, lay at his feet. Don’t kill him before he has been filled. They pried his mouth partially open, and the cement man began to fill it.

The townsfolk claim that the cement keeps the soul within the body, that without the cement, the soul would escape into the world. It’s clear, however, that the ritual is just a means to express their desires; they cherish the ceremony of killing. Instead of letting the dying pass naturally, they take the action into their own hands.

The narrator’s life is grim; he is acutely aware of the absurd traditions of his town, but he cannot escape them. It is the only society he knows, and society is convincing. He must become a man in this cruel village and ultimately come face-to-face with its greatest obsession: death.

The Village

The blacksmith told me the sundial used to stand in the middle of the Plaça; he had marked the hours and forged the pin in the center to signal them. A year later someone had stolen the pin, but no one cared; no one wanted time in their lives.

Seasons come and go and the village maintains its customs; every spring, they paint the houses in the village pink. They throw a festival. The men draw straws, and the one that pulls out the shortest one has to swim in the river that flows under the village.

Under the village are dangerous rapids. Most people who draw the short straw die. Some survive, but many of their bones are broken. Without doctors, their bodies heal deformed, and they are outcast by the village for the rest of their lives.

The village has almost no contact with the outside world other than an old man who peers down on the village from his house on the mountain top. He watches their rituals from his window, but never participates.

They also hold a prisoner: a “thief” imprisoned in a cage too small to either stand up or lay down. The townsfolk visit him with their families every Sunday. They toss him scraps of meat and laugh at his deterioration. The blacksmith says that the prisoner should only be released when he has become an animal.

On Sundays, many villagers went with their children to see the prisoner. They would toss him morsels of meat, close to the bars, and he had to catch the scraps with his mouth. If he couldn’t catch them, he had to pick them up from the ground with his teeth, like a horse eating grass. When no more meat could fit inside him, he would close his mouth and eyes, shutting the villagers out, and on the following day he would be punished. If it was summer the blacksmith would smear honey on him, and soon the prisoner became a fury of bees. Before honey could be smeared over his body, he would be seated in a bucket, his ankles and wrists tied with heavy rope to the bars of the cage.

The narrator goes to visit the thief often. He begins to question if he was actually a thief; nobody remembers what he stole or when, only that he was sentenced by the blacksmith. Although the prisoner often ignores him, one day he speaks to him directly.

He told me you had to live pretending to believe everything. Pretending to believe everything and doing everything others wanted; he’d been imprisoned when he was young because he knew the truth and spoke it.

It seems, then, that the prisoner was somebody who didn’t abide by the norms set by their society. Does that mean he’s a criminal? Should he be punished for not adhering to the town’s bizarre rules? What would happen to those who don’t lock their children in cupboards? Who don’t pour cement down their loved ones throats before death? Who refuse to risk their lives to swim under the village during the annual festival? These are all extreme versions of questions that Rodoreda believes we should be asking ourselves of our own society.

Thoughts

Society dictates how we see right or wrong. It dictates what languages we speak, what professions we have to choose from, and even how we interact with our families. It can be a support system for freedom and individuality or a rigid set of rules.

In the modern world, many of us may see it as a support system that enables us to live our lives. But can this simply mean that we have accepted the set of rules it has given us? Many well-off people in the past probably thought society was alright, all while Native Americans were being forced across the continent, African Americans were enslaved, and LGBTQs were persecuted.

Rodoreda was born in 1908. She was a woman born into a society that refused her right to vote, have property, and dictated who and what she was supposed to be. She witnessed her country being plunged into civil war to emerge into the hands of a cruel dictator for almost half a century. Death in Spring speaks for this and so much more.

Final Thoughts

Death in Spring is timeless. Even though it’s helpful to frame the novel within its historical context, its writing and themes are universal. The beauty and directness of Rodoreda’s prose and her insight into the cruel and oppressive sides of human nature make Death in Spring one of my favorite novels of all time.

It will make anybody, anywhere, contemplate the influence of society. How much of our lives is free will, versus things that society has taught and formed us to do? How would society react if we were to step outside of its rules? For those who already live oppressed by its rules, is death the only escape?

With the break of day, I saw death. I was death reflecting in the water the face of a dead person. I didn’t know why I thought that. Where does death begin? I asked myself. Did it spring from your skin or surface from beneath it? Was it at your fingertips, at that point in your entrails where the pain of life begins, at your elbow, in the center of your knee? Where did it begin to kill? Where did each person’s death reside?