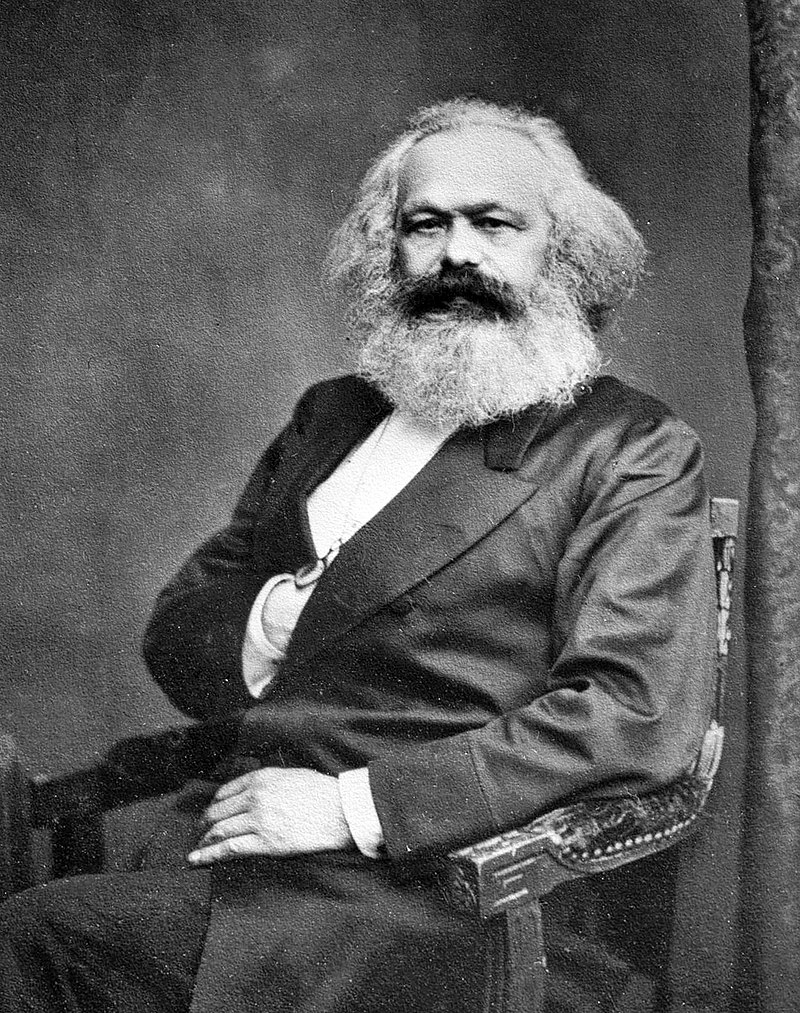

By John Jabez Edwin Mayal - International Institute of Social History, Public Domain, Link

Man makes religion, religion does not make man.

Philosophy dismantled the truth that religion pretended to offer. Truth and meaning – once pursued through the institutions of the church – were now pursued through different methods. These methods changed from “the criticism of religion into the criticism of right, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.”

This shift in thought made people feel alienated from the world that once seemed so straightforward.

Religion is the moan of the oppressed creature, the sentiment of a heartless world, as it is the spirit of spiritless conditions. It is the opium of the people…The abolition of religion, as the illusory happiness of the people, is the demand for their real happiness.

People could no longer hide behind the “illusion” of objectivity. Marx offers an alternative: since religion is made by man, philosophy – also made by man – can be the tool to bring meaning into people’s lives.

Germany

Marx shifts focus away from religion and towards critiquing the political atmosphere of mid-19th century Germany; Germany did not undergo emancipatory revolutions like the other European states during the Revolutions of 1948.

He believes that this was due to a disconnect between German philosophy and the political reality of its people.

We are philosophical contemporaries of the present without being its historical contemporaries. German philosophy is the ideal prolongation of German history.

Whereas German philosophy echoed the revolutionary sentiments of the other European states, their ideas did not find a foothold within the populace.

Theory becomes realized among a people only in so far as it represents the realization of that people’s needs. Will the immense cleavage between the demands of the German intellect and the responses of German actuality now involve a similar cleavage of middle-class society from the State, and from itself? Will theoretical needs merge directly into practical needs? It is not enough that the ideas press towards realization; reality itself must stimulate to thinking.

Even if these ideas were to find open ears, “political emancipation” can only be achieved if ideas correspond to urgent needs.

A radical revolution can only be the revolution of radical needs, whose preliminary conditions appear to be wholly lacking.

Marx argues that the only way for radical ideals to take hold of a population is to actually fulfill the needs of the population. “Revolutionary energy and intellectual self-confidence are not sufficient” for emancipation. But there is a deeper issue here; even if theory were to correspond with a set of needs, it is still not enough to truly wield emancipatory power.

To wield emancipatory power, the needs of one social class have to be the needs of all social classes under oppression. They must represent the “whole of society” to gain the support needed for emancipation.

No class in bourgeois society can play this part without setting up a wave of enthusiasm in itself and among the masses, a wave of feeling wherein it would fraternize and commingle with society in general, and would feel and be recognized as society’s general representative, a wave of enthusiasm wherein its claims and rights would be in truth the claims and rights of society itself, wherein it would really be the social head and the social heart. Only in the name of the general rights of society can a particular class vindicate for itself the general rulership.

In France, the nobility and clergy were once the oppressors of the bourgeoisie; the bourgeoisie assumed the role of the subjugated and pursued the “general rights of society.” The fact that they would later assume the role of oppressor is another story.

Marx believes that revolution did not take root in Germany because there was no class that represented the “whole of society.” In Germany, “each class, so soon as it embarks on a struggle with the class above it, becomes involved in the struggle with the class below it.”

If there is no cohesive group that can assume the “general rights of society,” how could emancipation take place?

Answer: In the formation of a class in radical chains, a class which finds itself in bourgeois society, but which is not of it, an order which shall break up all orders, a sphere which possesses a universal character by virtue of its universal suffering, which lays claim to no special right, because no particular wrong but wrong in general is committed upon it, which can no longer invoke a historical title, but only a human title, which stands not in a one-sided antagonism to the consequences, but in a many-sided antagonism to the assumptions of the German community, a sphere finally which cannot emancipate itself without emancipating all the other spheres of society, which represents in a word the complete loss of mankind, and can therefore only redeem itself through the complete redemption of mankind. The dissolution of society reduced to a special order is the proletariat.

The industrial revolution produced the proletariat. The proletariat – oppressed and subjugated not by the lack of resources, but by the unequal and unjust distribution of them – wants to abolish any private claim to those resources.

When the proletariat desires the negation of private property, it is merely elevating to a general principle of society what it already involuntarily embodies in itself as the negative product of society.

Circling back to the beginning of the essay, religion is no longer the influence it once was. Law and politics are the new methods of achieving meaning. Philosophy identified the proletariat, and the proletariat can use philosophy and these new methods of meaning to achieve its truth, meaning, and emancipation.

Just as philosophy finds in the proletariat its material weapons, so the proletariat finds in philosophy its intellectual weapons, and as soon as the lightning of thought has penetrated into the flaccid popular soil, the elevation of Germans into men will be accomplished.

Final Thoughts

Let us summarize the result at which we have arrived. The only liberation of Germany that is practical or possible is a liberation from the standpoint of the theory that declares man to be the supreme being of mankind. In Germany emancipation from the Middle Ages can only be effected by means of emancipation from the results of partial freedom from the Middle Ages. In Germany no brand of serfdom can be extirpated without extirpating every kind of serfdom. Fundamental Germany cannot be revolutionized without a revolution in its basis. The emancipation of Germans is the emancipation of mankind. The head of the emancipation is philosophy; the heart is the proletariat. Philosophy cannot be realized without the abolition of the proletariat, the proletariat cannot abolish itself without realizing philosophy.

A Criticism of the Hegelian Philosophy of Right is a good introduction into Marxist thought. Specifically, it defines the proletariat – a term referred to in a lot of his writing and socialist thought more broadly.

I believe that many people on the Left would agree to a large part of his writing here. What distinguishes this essay from less radical leftist views is the abolition of private property – briefly alluded to at the end of the essay.

This essay is part of Selected Essays published by Duke Classics and available in ebook in local libraries that use Overdrive.