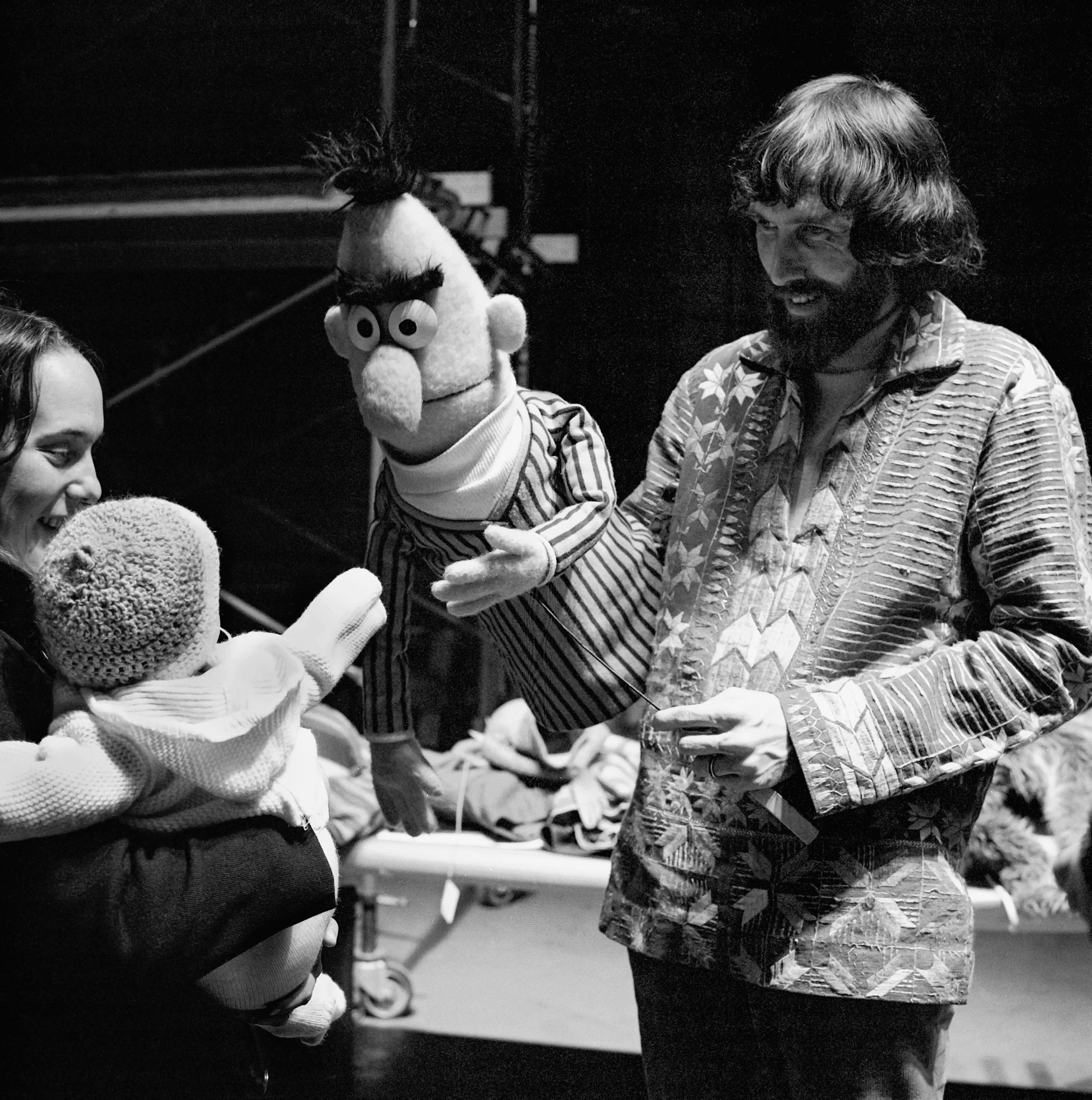

Photograph by David Attie

Jill Lepore is my favorite historian at the moment. She challenges the long-held belief in American, unrelenting progress by observing and critiquing popular aspects of our society.

In When Ernie Met Bert, Lepore uses the history of Sesame Street to critique the inevitable dominance of capitalism. She shows that during a time of unfettered capitalism where there was a “scarcity of preeschools and the abundance of televisions,” a group of educators got together to design a TV show for underprivileged youth.

Although Sesame Street was originally funded by government programs and shown on public television networks, Lepore traces how it would ultimately end up in the hands of Disney and shown exclusively on HBO for suburban households with the money to pay for it.

Origins

In the 1950s and 60s, the vast majority of American households had a television set. Children watched “a bleary-eyed average of fifty-four hours a week.” A group of educators saw this as a serious issue – and as an opportunity.

They got together with a New York-based public television channel to propose an educational show that would primarily target underprivileged youth.

Educational television for preschoolers seemed to solve two problems at once: the scarcity of preschools and the abundance of televisions.

This project ultimately went on to receive federal funding and turn into what we now know as Sesame Street. NBC and CBS – both for-profit companies – turned the show down. PBS – a non-profit, public broadcaster – picked it up. “Within weeks, Sesame Street was a cultural phenomenon.”

Most importantly, it listened to its viewers. Although it targeted diverse communities, in its early stages, it fell short in representing them. It was designed by ivy-league educators detached from the issues that many of its target communities faced.

They realized that they had to open their doors for community criticism. They listened to their audience and incorporated a slew of characters that went against mainstream conventions. They came from diverse backgrounds, had psychological issues, or were physically handicapped.

Some of these characters didn’t work out, but the important thing was that the creators listened to their audience and ultimately made Sesame Street into the phenomenon it’s known as today.

Despite the show’s rocky start, those early episodes are still the best television ever made for young children. The magnificence of its achievement was summed up by this magazine’s film critic Renata Adler, in 1972: “It is as though all the lessons of the New Deal federal planning and all the sixties experience of the ‘local people,’ the techniques of the totalitarian slogan and the American commercial, the devices of film and the cult of the famous, the research of educators and the talent of artists had combined in one small television experiment to sell, by means of television, the rational, the humane, and the linear to little children.” It doesn’t get any better than that.

The Fall

Although America certainly wasn’t the emblem of justice and equality in the 1960s and 70s, there were both grassroots and government programs to get there. Sesame Street was a conceited effort by individuals and the government working together to provide education to children coming from oppressed and disenfranchised backgrounds.

The Reagan years marked the beginning of the fall. The federal government all but stopped funding educational television in 1981, and deregulation meant that the F.C.C. accepted “The Flintstones” as fulfilling a station’s “educational” requirements. Kids’ TV in the nineteen-eighties involved mainly plastic toys: “My Little Pony’n Friends,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” “Sesame Street” became more commercial.

The surge of free-market, libertarian ideologies, the tearing down of government programs and initiatives, and the resulting accumulation of wealth in massive corporations lead to the commercialization of Sesame Street. Lepore indicates that this was a uniquely American occurrence, however, as many countries built on the fundamentals of Sesame Street for their own citizens.

Abroad, “Sesame Street” is still driven by the spirit of 1968. In the U.S., that spark has gone. The Muppets were sold to Disney, after which the Disney Channel launched a sickening animated series called “Muppet Babies,” a show so merchandise-driven that wittle, itty-bitty, never-witty Baby Kermit might as well talk with a price tag hanging off his face. Since 2015, “Sesame Street” has bee released first not on PBS but on HBO. A show designed as a public service, part of the War on Poverty, is now one you’ve got to pay for.

Final Thoughts

As Lepore does so well, she has taken a piece of history that many would see as inevitable and has shined a different light on it. Government deregulation gutted spending on public programs, which transformed Sesame Street from an educational show for kids all over America into a commercialized product exclusive to those who can afford it.

There are two typical responses to something like this. The first is a neutral, complacent attitude that it’s “just how the world is.” The other is an argument that capitalism is the natural order of things and that the government should not have their hand in making propaganda – that the free-market can produce it cheaper and more effectively.

I believe that both of these viewpoints are incorrect. Sesame Street could never have existed without the support of the government. The government doesn’t require a return on investment like companies do. Its investment is in the public itself – the education of its youth and the building of a better, more equal, and just society.

If this debate interests you, I recommend picking up this article. It’s a short, but eye-opening read.