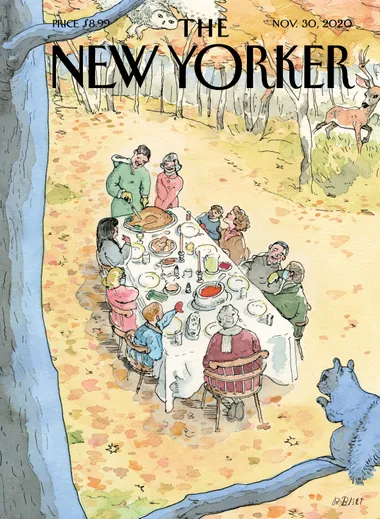

Cover: 'New Traditions' by Barry Blitt

If you have ever read one of William Faulkner’s books, The Sound and the Fury for example, I’d wager that Faulkner’s perspective on the South confused you. His characters range from wildly critical of their society – Quentin escapes his family and Mississipi town to study at a university in the North – to deeply faithful to its roots and culture.

And if you were to read Faulkner today, as the Black Lives Matter movement has once again succeeded in bringing racial justice to the forefront of American society, you may ask the question: was Faulkner racist? Should we hold his work in such high esteem, teaching it in schools as an exemplary form of fiction?

While some may dismiss these questions as irrelevant or bring up historical facts to justify their arguments - “Toni Morrison wrote her master’s thesis partly on Faulkner and his depictions of what she called ‘alienated’ individuals” – it’s important that we understand the difference between Faulkner’s personal life and the texts that live on in our collective consciousness.

This is exactly what Casey Cep considers in her article, Demon-Driven – which is itself a review of Michael Gorra’s new book, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War published by Liveright.

In “The Saddest Words,” Faulkner emerges as a character as tragic as any he invented: a writer who brilliantly portrayed the way that the South’s refusal to accept its defeat led to cultural decay, but a Southerner whose private letters and public statements were riddled with the very racism that his books so pointedly damned.

The man or his writing?

Faulkner’s interactions with the press do not give great confidence to his personal views. He has a wide range of commentaries that are completely bigoted in every sense.

He once “suggested that justice was delivered by juries and lynch mobs alike and that no innocent man of any race had ever been lynched.” He said that “Negros would be better off because they’d have someone to look after them” under the “benevolent autocracy” of slavery. And he claimed that “if it came to fighting, I’d fight for Mississippi against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.”

No mater the way you try to alter or justify these statements, the fact that Faulkner was racist will never become untrue. But who we are is never completely the fault of our own.

The schools we go to as children, the books we are given in classrooms, the way our families teach us right and wrong, live within us until our last days. We may outgrow them at times, see them for being wrong or harmful, or embrace them as part of our identity as an adult.

Maybe understanding this eternal, introspective struggle is what allows writers to depict the world around them so truthfully.

Rather than separating the artist from his art, Gorra suggests that the two are entwined; Faulkner’s racism informed his devastating portrayals of it…But there is no defending Faulkner’s character, only his characters. As the writer himself knew, the best art will always exceed the artist who creates it. Transcendence isn’t just an aesthetic experience for readers; it can be one for writers, too.

What Cep and Gorra are saying here, is that even though Faulkner was certainly racist himself, his writing “transcended” the facts of his personal life.

His writing took a snapshot of a dark time in our nation’s history from the perspective of those either in power, or directly benefiting from it. It taught us of the norms and perspectives of a society without reason.

But the only way to formulate those thoughts – to put them on paper so we could all see them clearly and say to ourselves “what are we doing here” – took a troubled man from this position of society.

Final Thoughts

My takeaway from this article is that great, everlasting fiction comes from portraying things how they really are – not how we want them to be, or how we suppose they should be, but from the brute reality of how they are.

It takes a writer who is deeply troubled, ingrained in a moment of time and bound by society’s influences, to look deeply into his or her heart and mind to describe truthfully what is going on around them.

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, Faulkner said that it was “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.”

While it would be absurd to dismiss Faulkner’s work because he was racist, it would be equally as absurd – or maybe even more so – to ignore Faulkner’s racism.

It’s a part of our historical record and a part of who we are as a society today. Our goal is to understand why it’s important to us and make sure that we are not approaching the topic with ignorance.

I enjoyed this article and will certainly consider picking up a copy of Gorra’s The Saddest Words – although I feel that type of book is typically more useful for academics or readers with a lot of time on their hands.

Cep’s article distilling the main points is incredibly useful for any fan of Faulkner, and it will certainly stay in my mind for his next book that I pick up, which will probably be Absalom Absalom!