Principles of Literary Criticism

Two Uses of Language, Poetry and Beliefs

part of the On Reading series

written by Jon Duelfer

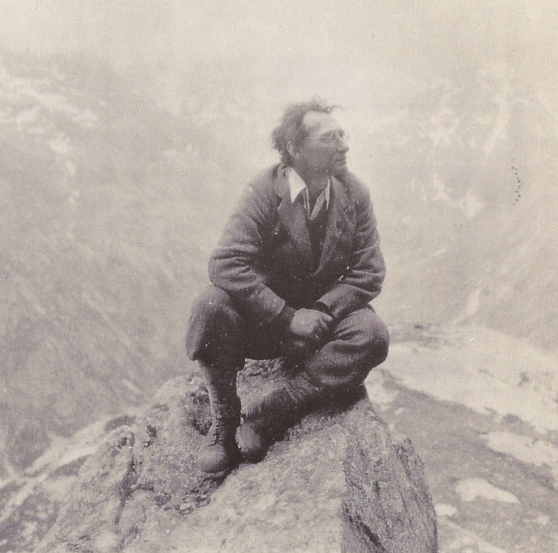

By © Richards family archive - Richards Archive, Magdalene College Cambridge, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=62038546

Better a plausible impossibility than an improbable possibility.

– Aristotle, Poetics

Principles of Literary Criticism is one of the first books of literary Formalism – the study of the individual components of a text. As a movement of thought, Formalism looked to critique texts not based upon subjective beliefs or prejudices, but instead to build a formal system based upon the independent elements of texts – such as metaphors, grammar, motifs, etc.

I. A. Richards brought a rigorous, scientific approach to building this system. He thought that literature is all about the experience of the reader, and the way that the reader reacts to the text is explained through psychology. Fiction answers biological needs that the reader cannot get out of an increasingly scientific, empirical world.

If fiction only answers our biological needs, would it then be subservient to the scientific pursuit of real truth? Richards would say that, no, fiction synthesizes and harmonizes conflicting needs in our psychology that science cannot provide us.

Both science and literature are worthy pursuits. Science is our mechanism of uncovering the world for our use of it. Literature is our mechanism for finding our place in the world. We need both to be human beings.

Here, I have focused on two chapters from Principles of Literary Criticism: The Two Uses of Language and Poetry and Beliefs, both excerpts from The Critical Tradition.

The Two Uses of Language

We may either use words for the sake of the references they promote, or we may use them for the sake of the attitudes and emotions which ensue.

Richards writes that human language is divided into two uses: the scientific and the emotive. Scientific language is used to reference real and true things in the world. It is 75 degrees. The ball weighs five pounds.

Emotive language is meant to provoke emotional responses in others. Fiction uses emotive language. Travel far enough, you meet yourself (from Cloud Atlas). The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for (from The Brothers Karamazov).

Both scientific and emotive language can hold truth, but the types of truth are different. A truth of science is “when the things to which it refers to are actually together in the way in which it refers to them.” A truth of fiction, however, is “the acceptability of things we are told, their acceptability in the interests of the effects of the narrative.”

We can see examples of both of these truths in Ernest Hemingway’s fictional novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. The Spanish Civil War took place in the 1930s. Hemingway was there. These are both facts that can be told using scientific language. Although the story is told through emotive language and is a fiction, it still seems to hold a sort of truth to it.

Truth may be equivalent to Sincerity.

What is real or true to us about a fiction is our acceptance of it. There is no factual, scientific truth that we can measure. It’s an overwhelming sense of understanding. The fiction tells us something about the the word that we live in that rings true within us.

Poetry and Beliefs

The separation of prose from poetry, if we may so paraphrase the distinction, is no mere academic activity. There is hardly a problem outside mathematics which is not complicated by its neglect, and hardly any emotional response which is not crippled by irrelevant intrusions.

Richards argues that prose, in comparison to poetry, introduces scientific language that pulls away from a completely emotive response. Poetry is entirely emotive language.

Poetry can grasp a deeper set of emotions. How does it do this? Richards says that it thrives on our beliefs.

For example, a historical fiction set during the American Revolutionary War will use scientific and emotive language. It distances itself from the reader’s emotions by asserting dates, times, actual events and then filling in between with fiction.

The Star Spangled Banner, although written for a different war, conveys much more emotion about American freedom and liberty. “O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave” definitely sparks more emotions in its few sentences than pages and pages of a forgotten novel.

Poems are tied to a set of beliefs that we already hold. The poem’s job is not to convince us that freedom and liberty are ideals we should hold, but to reinforce the beliefs that we already have by triggering an emotional response to them.

There is a suppressed conditional clause implicit in all of poetry. If things were such and such…and so the response develops. The amplitude and fineness of the response, its sanction and authority, in other words, depend upon this freedom from actual assertion in all cases in which the belief is questionable on any ground whatsoever.

Richards says that a good poem doesn’t need to assert something for the reader to understand it. In fact, “assertion is almost always unnecessary; if we look closely we find that the greatest poets, as poets, though frequently not as critics, refrain from assertion.” Poetry should understand our implicit beliefs and thrive on them.

Beliefs are slippery; they can be political (socialism vs. capitalism), scientific (the world is round), or even poetic (the mountains are most beautiful at dusk). But what is their relationship with art?

Very often the whole state of mind in which we are left by a poem, or by music, or, more rarely perhaps, by other forms of art, is of a kind which it is natural to describe as a belief.

Coming back around to the example of For Whom the Bell Tolls, after finishing the novel, we may believe that war fosters camaraderie. Hemingway was not the first to say this; he uses a belief that humans have long held throughout our history. But through the strength of his narrative, we believe it to be truth.

…the arts seem to lift away the burden of existence, and we seem ourselves to be looking into the heart of things. To be seeing whatever it is as it really is, to be cleared in vision and to be recipients of a revelation.

That “war fosters camaraderie” may be scientifically true. There may be neurological studies that show our brains undergo change during heightened anxiety or near-death experiences to be more open to companionship. But this is not what For Whom the Bell Tolls is pursing. It’s not pursuing scientific truth; it’s pursing emotive truth.

Richards concludes the chapter making the distinction between Knowledge and Beauty. Knowledge is scientific truth. Beauty is the truth we feel from the arts. Hemingway’s truth that war fosters camaraderie, then, is Beauty.

Questions and Concerns

These two chapters from Richards’s Principles of Literary Criticism are a great introduction to literary Formalism. I do have some questions and concerns that go unanswered, though.

Only Two Uses of Language

There are clearly more than two uses of language; there is persuasive language, deceptive language, commanding language, and a number of other pragmatic categories that are not taken into account in this theory of literature.

The case could be made that all of these categories somehow fit into scientific or emotive language, but this would not be a useful categorization. This dichotomy is a helpful metaphor to think about literature, but I don’t think it has scientific truth to it.

All language was originally emotive

…there can be no doubt that originally all language was emotive; its scientific use is a later development, and most language is still emotive. Yet the late development has come to seem the natural and the normal use, largely because the only people who have reflected upon language were at the moment of reflection using it scientifically.

This is false. The field of linguistics has shown this simply not to be true. We do have to remember that this book was written way before linguistics really took off as a field of study (and actually contributed a lot to its popularity). Hearing something so outrageous as this, though, make me question the rest of the text.

Prose is less emotive

Richards makes the argument that prose is less emotive than poetry. He argues this by saying prose pulls in scientific language and makes statements and assertions where poetry is pure, emotive language.

Because Richards was a psychologist, I get why he saw poetry as being closer to emotions than prose. When we read poetry, it sparks more instantaneous emotions, more like stimuli. Prose builds on a flatter set of emotions over time. I don’t think either is more “emotive” language than the other though.

Poems shouldn’t assert

If poems shouldn’t assert, whose set of beliefs are we playing to? Is evaluation simply dependent on who holds the belief? So the most valued works will be those that abide by the beliefs of those wielding the most power?

Final Thoughts

Richards’s classifications of scientific and emotive language, poetry and prose, and Knowledge and Beauty are helpful when considering the theory of literature. Although I believe these dichotomies are too simplistic and leave out much of the pragmatic use of language, he made a step forward in creating a formal system.

Formalism attempts to look inside the black box of creativity and understand what makes literature what it is. Why does some writing ring true with us while other writing doesn’t? Richards makes a strong point that it’s using our underlying beliefs.

I would argue, though, that some of the best literature is that which instills a new belief system, or shows us something as we had never seen it before. Maybe it does use our existing belief system to wiggle in and get our acceptance, but I don’t believe that the greatest poets “refrain from assertions.” I believe the most popular poets within a certain belief system refrain from assertions that challenge belief system. That does not make them the “greatest poets.”